Islahhane - the new investment challenge in Bitola

Bitola, 31 May 2021 (MIA) - Islahhane are schools that were built across the Ottoman Empire in 1860. At the time, the first islahhane was built in Nish in the Balkan area, then in Skopje, and the Bitola islahane was built from 1894 to 1899 and it was opened on October 6, 1902, staying in use until 1912. A preserved islahhane exists in Thessaloniki too.

The word islahhane comes from the Turkish word islah which means “good”, and hane which means “place”. Its full meaning is “good place”.

Architecturally, this monumental building is in the neoclassical and neo-Renaissance style, identical to many public institutions during the rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid, greatly influenced by the Parisian school. All islahhanes and idadias were built by the Ministry of Urbanism at the time, in accordance with the size of the city and the population. It’s mainly a state empire architecture, two stories with three rows of symmetrically placed rectangular windows, and the entrance to the building was decorated with pillars and big steps that made the building look grandiose.

“The Bitola and Thessaloniki islahhane are the last two preserved buildings in the Balkans. Unfortunately, war, time, and neglect had affected this building, which is now placed under protection after a suggestion of the Bitola Institute and Museum, with an act adopted by the Administration for Protection of Cultural Heritage. The act determines the building’s borders and contact zone, as well as its protection regimen, i.e. the limitations that come with its protected status, Culture Minister Irena Stefoska has said.

The deadline for temporary protection is one year, she has added, and Institution and Museum need to create a valorization elaborate, which will enable the possibility to bring an act of permanent protection as a cultural heritage. The building is for sale, but it’s protected regardless of its owner being a private or a state institution. Protection doesn’t depend on that. The building must be protected in accordance with all rules and principles of protection of a cultural good.

The building played huge role in the development of Bitola’s socio-economic state, because the children at the trade school, apart from elementary education, would hone trading skills, and the talented children would be selected to work at the big industrial capacities and city trading.

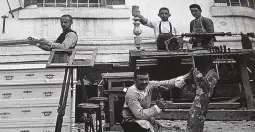

From a preserved photo by the Manaki brothers, found at the Archive by researcher Robert Jankulovski, recently promoted by the Ministry of Culture, it can be seen that the Bitola islahhane was an industrial school where locksmithing, shoemaking, carpentry and sewing was taught, adding arts into the mix later on. The islahhane worked according to a regulated statute, and the concept of its management and working was based on the newest reforms of the Ottoman Empire that largely relied on the contribution of the islahhane in order to clean up the city, regulate the streets and protect the ambience.

From a preserved photo by the Manaki brothers, found at the Archive by researcher Robert Jankulovski, recently promoted by the Ministry of Culture, it can be seen that the Bitola islahhane was an industrial school where locksmithing, shoemaking, carpentry and sewing was taught, adding arts into the mix later on. The islahhane worked according to a regulated statute, and the concept of its management and working was based on the newest reforms of the Ottoman Empire that largely relied on the contribution of the islahhane in order to clean up the city, regulate the streets and protect the ambience.

“From the point of view of conservatorship, the trade school Islahhane has been a registered facility for a long time, representing an integral part of a sector study related to the cultural heritage in Bitola. Alongside this study where this cultural good is registered, in 2016, experts from the Bitola Institute and Museum made protective conservational basics for this part of the town which includes the former islahhane, known among the people of Bitola as the ‘Old Progress’ building. The protection of a building is not related to its ownership, only to the building itself. The protection regimen for this cultural monument concretely stipulates all procedures that can and must be followed in the domain of its protection,” says Meri Stojanova, director of the Bitola Institute and Museum.

“From the point of view of conservatorship, the trade school Islahhane has been a registered facility for a long time, representing an integral part of a sector study related to the cultural heritage in Bitola. Alongside this study where this cultural good is registered, in 2016, experts from the Bitola Institute and Museum made protective conservational basics for this part of the town which includes the former islahhane, known among the people of Bitola as the ‘Old Progress’ building. The protection of a building is not related to its ownership, only to the building itself. The protection regimen for this cultural monument concretely stipulates all procedures that can and must be followed in the domain of its protection,” says Meri Stojanova, director of the Bitola Institute and Museum.

The trade school in Bitola was built after a firman issued by Sultan Abdul Hamid, and its name was Industrial Mehtab or Hamidye.

120 years later, it faces an investment challenge due to its complex past and colorful future.

Marjan Tanushevski

Translated by Dragana Knezhevikj

The trade school in Bitola was built after a firman issued by Sultan Abdul Hamid, and its name was Industrial Mehtab or Hamidye.

120 years later, it faces an investment challenge due to its complex past and colorful future.

Marjan Tanushevski

Translated by Dragana Knezhevikj

From a preserved photo by the Manaki brothers, found at the Archive by researcher Robert Jankulovski, recently promoted by the Ministry of Culture, it can be seen that the Bitola islahhane was an industrial school where locksmithing, shoemaking, carpentry and sewing was taught, adding arts into the mix later on. The islahhane worked according to a regulated statute, and the concept of its management and working was based on the newest reforms of the Ottoman Empire that largely relied on the contribution of the islahhane in order to clean up the city, regulate the streets and protect the ambience.

From a preserved photo by the Manaki brothers, found at the Archive by researcher Robert Jankulovski, recently promoted by the Ministry of Culture, it can be seen that the Bitola islahhane was an industrial school where locksmithing, shoemaking, carpentry and sewing was taught, adding arts into the mix later on. The islahhane worked according to a regulated statute, and the concept of its management and working was based on the newest reforms of the Ottoman Empire that largely relied on the contribution of the islahhane in order to clean up the city, regulate the streets and protect the ambience.

“From the point of view of conservatorship, the trade school Islahhane has been a registered facility for a long time, representing an integral part of a sector study related to the cultural heritage in Bitola. Alongside this study where this cultural good is registered, in 2016, experts from the Bitola Institute and Museum made protective conservational basics for this part of the town which includes the former islahhane, known among the people of Bitola as the ‘Old Progress’ building. The protection of a building is not related to its ownership, only to the building itself. The protection regimen for this cultural monument concretely stipulates all procedures that can and must be followed in the domain of its protection,” says Meri Stojanova, director of the Bitola Institute and Museum.

“From the point of view of conservatorship, the trade school Islahhane has been a registered facility for a long time, representing an integral part of a sector study related to the cultural heritage in Bitola. Alongside this study where this cultural good is registered, in 2016, experts from the Bitola Institute and Museum made protective conservational basics for this part of the town which includes the former islahhane, known among the people of Bitola as the ‘Old Progress’ building. The protection of a building is not related to its ownership, only to the building itself. The protection regimen for this cultural monument concretely stipulates all procedures that can and must be followed in the domain of its protection,” says Meri Stojanova, director of the Bitola Institute and Museum.

The trade school in Bitola was built after a firman issued by Sultan Abdul Hamid, and its name was Industrial Mehtab or Hamidye.

120 years later, it faces an investment challenge due to its complex past and colorful future.

Marjan Tanushevski

Translated by Dragana Knezhevikj

The trade school in Bitola was built after a firman issued by Sultan Abdul Hamid, and its name was Industrial Mehtab or Hamidye.

120 years later, it faces an investment challenge due to its complex past and colorful future.

Marjan Tanushevski

Translated by Dragana Knezhevikj