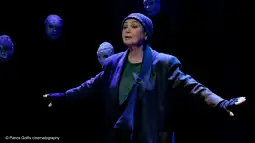

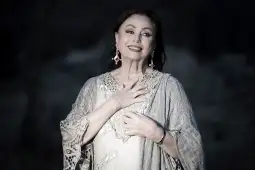

Greek actress and singer Georgia Zoi for MIA: History often silences those it exploits

- "I deeply believe in cultural exchange in the Balkans and welcome future collaborations. My first contact with your country was last year through Goce Ristovski, who was a member of the jury at the International Monologue Festival in Kosovo. This interview is my second connection - and I am truly honored," says the popular Zoe

Skopje, 14 February 2026 (MIA) — Georgia Zoi is a famous Greek actress and singer, with an impressive long-standing career in theater, film, television and music. She has been active on stage for over four decades, both in Greece and abroad. She studied architecture and dramatic arts, graduating with honors and receiving scholarships from the State Scholarship Foundation of the National Technical University Academy (NTUA) and the Drama School of the National Theatre of Greece.

She has performed in over 62 theater productions, 24 films (including "Sun of Death", "Red Train", "Fate"... and her last film "Huzun" was nominated for an Oscar in 2023), 18 television series from the 1970s onwards.

In addition to acting, Zoe is also involved in singing, especially traditional Greek songs and musical performances in theater and concert contexts. She has performed at international festivals, including collaborations with famous musical artists and performances of songs such as the hyper-popular "My Gianni, Your Scarf."

This charming and charismatic doyenne of the Greek art scene is the recipient of numerous awards, such as the Best Actress Award at the Alexandria Festival (1980), the Theathopios Means Light Award for lifetime contribution to theater (2018), two UNESCO awards (2018 and 2019) for performances in theatrical plays, the Pegasus Award at the International Film Festival "Bridges" in Corinth (2021), the recognition for overall contribution to Greek art from the Hellenic Academy of Art Awards (2023)...

And she was often part of Greek delegations to world architecture congresses and other international forums as a lecturer on architecture and the environment.

What made you choose acting as your calling in life?

Acting was not a sudden choice but a gradual necessity. From a very young age, I felt the need to understand human behavior, contradictions, silence, and speech.

I was fifteen years old when I first came into contact with theater through ancient tragedy, while still in high school. I immediately dived into deep waters: I played “Andromache” in Euripides’ “Troades”, and the following year “Medea” in a large open-air arena.

What is perhaps paradoxical is that I first performed theater as an actress before I ever experienced it as a spectator. At that time, we lived in small villages and towns without theaters, so my first real encounter with theater was on stage, not in the audience. Only later did I discover theater as a spectator in larger cities.

Although I was an excellent student and initially studied architecture at the Technical University of Athens, theater offered me a space where questions mattered more than answers. It became a way of being in the world with awareness and responsibility. After completing my architectural studies, I continued my education at the National Theatre of Greece.

You have experience in theater, film and television. Where do you feel most free as an artist and why?

Theater is where I feel most free. It is a living art form based on presence, risk, and direct communication with the audience. There is no mediation, no editing—only truth in the moment.

What moment in your career do you consider a turning point?

There were several moments, but three monologues stand out.

The first was Gaia by Yannis Falconis, a heartbreaking monologue presented for the first time worldwide in the sea. I portrayed a refugee woman who survives a shipwreck, rescues a foreign baby, and makes it her life’s mission to find him a hospitable land. The sea itself became the stage, while the audience stood on the shore. The performance was presented in Lefkada, Nidri, Venice (in front of the Venice Biennale and at the Lido, near the Venice Film Festival), and in the Arachthos River. Later, it was also performed in winter in theaters, using an inflatable pool transformed into a sea. I performed entirely in cold water.

The second was Amber Alert by Odise Plaku, which earned me an international award last year as Best Actress at the International Monologue Festival in Kosovo.

The third is The Beautiful Helen in the Valley of Dead Love by Konstantinos Bouras, which premiered on January 13 at the Athens Concert Hall and now continues at the Radar Theatre.

All three demanded absolute exposure and responsibility and marked a deeper maturity in my artistic journey.

How has Greek theater changed from the beginning of your career to today?

Greek theater has become more outward-looking and experimental, despite financial difficulties. There is a strong new generation of artists and a continuous dialogue with ancient drama, which remains our living backbone.

This dialogue is also present in my latest performance, where Euripides’ “Helen” appears “aged,” speaking her own truths—about violence against women, injustice, rape, loss, war, and refugees—with the hope that peace may prevail. She is no longer “Helen of Troy, but “Helen of Peace”.

You are also a graduate architect who has actively practiced architecture for decades. How does architecture influence your approach to roles and stage space?

Architecture teaches structure, proportion, and the relationship between body and space. When I approach a role, I think spatially: where the character stands, how the body moves, how silence occupies space. A role, for me, is also a construction.

I have literally united these two identities—architect and actress—by designing theaters myself. I have designed several theaters, both small and large, including the open-air stone Floka Theatre in Ancient Olympia (3,000 seats), the Municipal Theatre of Kalamaria “Melina Mercouri” in Thessaloniki, and smaller theaters in Athens such as Eler, Theatriki Skini Antoni Antoniou, Viktoria, and of course the Radar Theatre. This year, ten years after its opening, I will perform there for the first time, which moves me deeply.

Have you ever felt a conflict between the rational world of architecture and the emotional world of acting?

No. I see them as complementary. Architecture provides discipline and clarity; acting allows emotional truth. Both require precision and imagination.

If you could “design” the perfect theater, what would it look like?

It would be simple, human-scaled, and flexible—a space that brings the audience close to the performer, where nothing hides behind technology, only presence and breath. Radar is one such theater.

It saddens me that even spaces with perfect acoustics, such as the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus, sometimes rely unnecessarily on technology.

Which role challenged you the most emotionally or psychologically?

“Amber Alert” was extremely demanding. It dealt with violence, trauma, loss, and silence. Carrying that material night after night required great inner discipline.

Is there a character you have played that still lives within you?

“Helen”—not as a myth, but as a woman who finally speaks. She remains with me as a reminder of how history often silences those it uses.

How do you prepare for roles in ancient tragedy compared to contemporary texts?

Ancient tragedy requires listening to rhythm, breath, and collective memory. Contemporary texts demand intimacy and psychological detail. The discipline differs, but the responsibility remains the same.

What is the difference between audiences at international festivals and Greek audiences?

International audiences often approach a performance without cultural preconceptions, creating an open dialogue. Greek audiences carry deep historical memory, which adds another layer of intensity.

In both cases, the actor must win the audience with body, voice, and soul. I experienced this profoundly in Tirana and Pristina with Amber Alert, where I performed in Greek and the audience remained deeply moved long after the performance ended.

What does it mean to you when your work is recognized by major International Festivals or Institutions such as UNESCO?

Recognition is an honor, but not a goal. What matters most is that the work travels, communicates, and opens dialogue across borders.

Do you feel that Greek culture is sufficiently represented on the world stage?

Greek culture is respected, but it needs a continuous contemporary presence—not only through the past, but also through today’s artistic voices.

With this goal in mind, all the contributors of “The Beautiful Helen in the Valley of Dead Love”—author Dr. Konstantinos Bouras, director Kostis Kapelonis, composer and on-stage soloist Zoe Tiganouria, percussion soloist Stelios Generalis, set designer Sofia Pagoni, choreographer Zefi Bartzoka, and myself—decided, with the auspices of four Greek ministries, to travel to Europe and America to communicate Greek culture internationally. It would be a great honor for us to perform in your country as well.

You are also a singer. How does the voice function as a tool in acting?

The voice carries memory, emotion, and truth. It can reveal what words hide. For me, singing and acting are deeply connected.

In my latest performance, “The Beautiful Helen in the Valley of Dead Love”, a poetic musical-theatrical work, I sing nine songs—four traditional and five contemporary compositions inspired by traditional Greek music.

How important is the body as an instrument in theater today?

The body is central. In an age dominated by screens, the physical presence of the actor is a political and poetic act.

What keeps you creatively active after so many years on stage?

Curiosity, discipline, and daily practice. My personal daily practice is swimming. On February 3, I completed fifteen years of continuous daily swimming without a single day off, always in natural environments—seas, rivers, and lakes.

During swimming, I rehearse my roles; the water becomes an immense stage, with birds, seagulls—and sometimes dolphins and swans—as spectators. I believe creativity is a form of training, not inspiration alone.

Can art change society, or at least the way people think?

Art may not change the world directly, but it can change perception—and that is where every real change begins.

How do you deal with silence and breaks between projects?

Silence is necessary. It allows reflection, preparation, and renewal. I respect it as part of the creative process. I have gone through periods of creative silence before, but in recent years I have been working in theater almost breathlessly—as if there is no tomorrow.

What would you say to young actors starting their journey?

Be patient, work consistently, avoid shortcuts, and remain passionate. Depth comes with time and honesty.

Is there still a role or project that you dream of realizing?

Yes. Projects that bring together theater, music, and space—where different arts speak one language, understood by people everywhere.

Do you collaborate with institutions or colleagues from North Macedonia?

I deeply believe in cultural exchange within the Balkans and welcome future collaborations. My first contact with your country was last year through Goce Ristovski, who served on the jury of the International Monologue Festival in Kosovo.

This interview is my second connection—and I am truly honored by it.

Branka D. Najdovska